Most everyone knows that Jackie Robinson was the first African-American to play major league baseball during the modern era. Surprisingly, few people have given much thought to how Robinson came to the attention of major league scouts, where he played before signing with the Dodgers, or just what the nature of baseball in the black community might have been before professional baseball’s integration.

In the following paragraphs, we’ll take a quick trip through the years of baseball in black America that led up to Robinson’s 1947 debut in Brooklyn.

Most everyone knows that Jackie Robinson was the first African-American to play major league baseball during the modern era. Surprisingly, few people have given much thought to how Robinson came to the attention of major league scouts, where he played before signing with the Dodgers, or just what the nature of baseball in the black community might have been before professional baseball’s integration.

In the following paragraphs, we’ll take a quick trip through the years of baseball in black America that led up to Robinson’s 1947 debut in Brooklyn. Our tour is intended to introduce those who are just learning about the Negro Leagues to this fascinating era in the history of American sports and society.

There won’t be much here to interest the baseball aficionado — just a brief introduction for those newly discovering Negro League baseball.

1. The Baseball World Before 1890

While it would be quite a stretch to say that professional baseball in the North was integrated between the end of the Civil War and 1890, quite a number of African-Americans played alongside white athletes on minor league and major league teams during the period. Although the original National Association of Base Ball Players, formed in 1867, had banned black athletes, by the late 1870s several African-American players were active on the rosters of white, minor league teams. Most of these players fell victim to regional prejudices and an unofficial color ban after brief stays with white teams, but some notable exceptions built long and solid careers in white professional baseball.

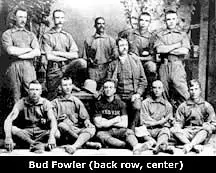

In 1884 the Stillwater, Minnesota club in the Northwestern league signed John W. “Bud” Fowler, an African-American with more than a decade’s experience as an itinerate, professional player. Fowler, a second-baseman by preference, played virtually every position on the field for Stillwater, enhancing the reputation that had brought him to the attention of white team owners. Fowler’s baseball career continued through the end of the 19th Century, much of it spent on the rosters of minor league clubs in organized baseball.

In 1883 former Oberlin College star Moses “Fleetwood” Walker began his professional career with Toledo in the Northwestern League. A more than average hitter, Walker was among baseball’s finest catchers almost from the beginning of his career. When the Toledo club joined the American Association in 1884 Walker became the first black player to play with a major league franchise.

In 1886 both Walker and Fowler were in the white minor leagues along with two other black stars, George Stovey and Frank Grant. Doubtless, many other black players were playing with teams in the “outlaw” leagues and independent barnstorming clubs. At least in the North and Midwest, the best black players found a measure of tolerance, if not acceptance, in white baseball until the end of the 1880s. But in 1890 this situation abruptly changed.

As the season of 1890 began there were no black players in the International League, the most prestigious of the minor league circuits. Without making a formal announcement, a gentlemen’s agreement had been made which would bar black players from participation for the next fifty-five years. Though black players continued to find work in lesser leagues for a time, within only a few short years no team in organized baseball would accept black players. By the turn of the century, the color barrier was firmly in place.

2. Professional Black Baseball Comes To The Fore

While Fowler, Walker, Grant, and others were working to find a spot (and keep it) in organized baseball, other black players were pursuing careers with the more than 200 all-black independent teams that performed throughout the country from the early 1880s forward. Eastern teams like the powerful Cuban Giants, Cuban X Giants, and Harrisburg Giants played both independently and in loosely organized leagues through the end of the century, and in the early 1900s professional black baseball began to blossom throughout America’s heartland and even in the South.

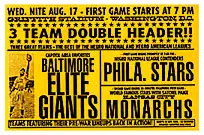

The early years of the 20th Century saw the emergence of several powerful black clubs in the Midwest. Teams like the Chicago Giants, Indianapolis ABCs, St. Louis Giants, and Kansas City Monarchs rose to prominence and presented a legitimate challenge to the claim of diamond supremacy made by Eastern clubs like the Lincoln Giants in New York, Brooklyn Royal Giants, Cuban Stars, and Homestead (Pa.) Grays. In the South, black baseball was flourishing in Birmingham’s industrial leagues, and teams like the Nashville Standard Giants and Birmingham Black Barons were establishing solid regional reputations.

By the end of World War I black baseball had become, perhaps, the number one entertainment attraction for urban black populations throughout the country. It was at that time that Andrew “Rube” Foster, owner of the Chicago American Giants and black baseball’s most influential personality, determined that the time had arrived for a truly organized and stable Negro league. Under Foster’s leadership in 1920, the Negro National League was born in Kansas City, fielding eight teams: Chicago American Giants, Chicago Giants, Cuban Stars, Dayton Marcos, Detroit Stars, Indianapolis ABCs, Kansas City Monarchs, and St. Louis Giants.

In the same year Thomas T. Wilson, owner of the Nashville Elite Giants, organized the Negro Southern League with teams in Nashville, Atlanta, Birmingham, Memphis, Montgomery, and New Orleans. Only three years later the Eastern Colored League was formed in1923 featuring the Hilldale Club, Cuban Stars (East), Brooklyn Royal Giants, Bacharach Giants, Lincoln Giants, and Baltimore Black Sox.

The Negro National League continued on a sound footing for most of the 1920s, ultimately succumbing to the financial pressures of the Great Depression and dissolving after the 1931 season. The second Negro National League, organized by Pittsburgh bar owner Gus Greenlee, quickly took up where Foster’s league left off and became the dominant force in black baseball from 1933 through 1949.

The Negro Southern League was in continuous operation from 1920 through the 1940s and held the position as black baseball’s only operating major circuit for the 1931 season. In 1937 the Negro American League was launched, bringing into its fold the best clubs in the South and Midwest, and stood as the opposing circuit to Greenlee’s Negro National League until the latter league disbanded after the 1949 season.

Despite the difficult economic challenges posed to the entire nation by the Depression, the three major Negro League circuits weathered the storm and steadily built what was to become one of the largest and most successful black-owned enterprises in America. The existence and success of these leagues stood as a testament to the determination and resolve of black America to forge ahead in the face of racial segregation and social disadvantage.

3. The Golden Years Of Black Baseball

When Gus Greenlee organized the new Negro National League in 1933 it was his firm intention to field the most powerful baseball team in America. He may well have achieved his goal. In 1935 his Pittsburgh Crawfords lineup showcased the talents of no fewer than five future Hall-Of-Famers – Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, Judy Johnson, and Oscar Charleston.

While the Crawfords were, undoubtedly, black baseball’s premier team during the mid-1930s, by the end of the decade Cumberland Posey’s Homestead Grays had wrested the title from the Crawfords, winning 9 consecutive Negro National League titles from the late 1930s through the mid-1940s. Featuring former Crawfords stars Gibson and Bell, the Grays augmented their lineup with Hall-Of-Fame talent such as that of power-hitting first baseman Buck Leonard.

Contributing greatly to the ever-growing national popularity of Negro League baseball during the 1930s and 1940s was the East-West All-Star game played annually at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. Originally conceived as a promotional tool by Gus Greenlee in 1933, the game quickly became black baseball’s most popular attraction and biggest money maker. From the first game forward the East-West classic regularly packed Comiskey Park while showcasing the Negro League’s finest talent.

As World War II came to a close and the demands for social justice swelled throughout the country, many felt that it could not be long until baseball’s color barrier would come crashing down. Not only had African-Americans proven themselves on the battlefield and seized an indisputable moral claim to an equal share in American life, the black baseball stars had proven their skills in venues like the East-West Classic and countless exhibition games against major league stars. The time for integration had come.

4. The Color Barrier Is Broken

Baseball’s color barrier cracked on April 18, 1946 when Jackie Robinson, signed to the Dodgers organization by owner Branch Rickey, made his first appearance with the Montreal Royals in the International League. After a single season with Montreal, Robinson joined the parent club and helped propel the Dodgers to a National League pennant. Along the way, he also earned National League Rookie Of The Year honors.

Robinson’s success opened the floodgates for a steady stream of black players into organized baseball. Robinson was shortly joined in Brooklyn by Negro League stars Roy Campanella, Joe Black, and Don Newcombe, and Larry Doby became the American League‘s first black star with the Cleveland Indians. By 1952 there were 150 black players in organized baseball, and the “cream of the crop” had been lured from Negro League rosters to the integrated minors and majors.

During the four years immediately following Robinson’s debut with the Dodgers virtually all of the Negro League’s best talent had either left the league for opportunities with integrated teams or had grown too old to attract the attention of major league scouts. With this sudden and dramatic departure of talent, black team owners witnessed a financially devastating decline in attendance at Negro League games. The attention of black fans had forever turned to the integrated major leagues, and the handwriting was on the wall for the Negro Leagues.

The Negro National League disbanded after the 1949 season, never to return. After a long and successful run, black baseball’s senior circuit was no longer a viable commercial enterprise. Though the Negro American League continued on throughout the 1950s, it had lost the bulk of its talent and virtually all of its fan appeal. After a decade of operating as a shadow of its former self, the league closed its doors for good in 1962.